Chicago, IL - In a victory for the Lucy Parsons Labs, Cook County Judge Kathleen G. Kennedy rejected the Chicago Police Department’s motions to dismiss a lawsuit related to Stingray deployments. Freddy Martinez brought the lawsuit against the Chicago Police Department in September 2014 to produce records on how the Chicago Police deploys IMSI Catchers in Chicago under Illinois FOIA law. Lawyers from the City of Chicago, which represented CPD in the suit, had moved to dismiss the lawsuit with their motions denied by Judge Kennedy in a nineteen-page opinion.

Among the arguments presented by the City of Chicago was that court authorizations for IMSI Catcher deployments would be sealed under US Code 18 USC 3123(d)(1) for Pen Register/Trap and Trace orders. The City of Chicago further argued the City’s FOIA department should not be responsible but that the plaintiffs should petition those courts to unseal the order. This presents a circular argument for maintaining secrecy; a petitioner doesn’t know in which cases Stingrays were used and in which courts, making it unclear who to petition to unseal the order. Judge Kennedy rejected this argument, because as we know, IMSI catchers are not pen register devices. Their capabilities are more powerful: Stingrays can capture Dialed Number Records (DNRs), perform real-time location tracking, capture text message information and even voice content (it is unclear if any US-based police forces have this software upgrade, but the hardware has this capability as seen in “national security” operations). Judge Kennedy wrote in her opinion:

The record reflects that a pen register is a device that records the numbers dialed by a particular telephone, and a trap and trace device records the incoming numbers to a telephone. Further, the record reflects that IMSI Catchers, also known as cell site simulators or stingrays, can capture a cell phones unique serial number, its location, and the content of calls, text messages, and web pages visited. Because IMSI catchers’ capabilities are broader, it is improper to equate them to and treat them as pen registers and trap and trace devices. Thus, to the extent that orders address technology other than pen registers and trap and trace devices, they are not exempt under section based on 18 USC 3123(d)(1).

The City of Chicago presented additional arguments that releasing information of how Stingrays are deployed would harm national security. As we’ve seen since 9/11, the State is quick to draw on “national security” as a justification for a wide range of mass surveillance programs, from PRISM and social media monitoring to the war on drugs. In support of the Chicago Police Department’s argument was an affidavit from FBI agent Morrison who in fact has submitted the exact same affidavit in various other cases. Judge Kennedy also rejected this argument under Day, writing in her opinion that “affidavits will not suffice to prove an exemption based on statements that are ‘conclusory, merely recite statutory standards, and are too vague or sweeping.’” (page 14) In essence, this was a boiler-plate affidavit and inapplicable as to how Chicago specifically deploys Stingrays.

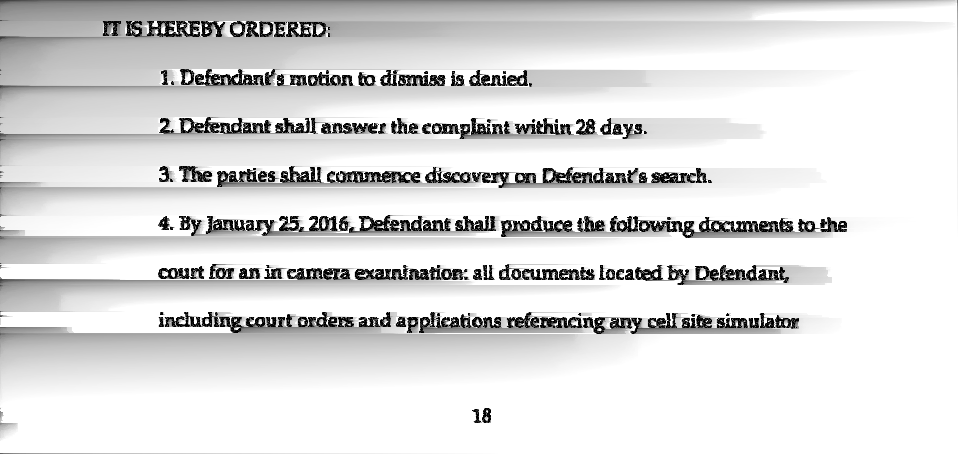

It was therefore ruled that the Chicago Police Department must produce responsive records to Judge Kennedy by January 25th, at which time she will review the documents in camera and then rule which records are exempt from disclosure. Lucy Parsons Labs will share more information in this space as we gather it.

The Lucy Parsons Labs would like to express our thanks to Matt Topic, Josh Burday, Andy Thayer, the entire Loevy and Loevy firm, Craig Futterman and his legal assistants (we apologize for not having the exact names of those assistants.)

Twitter Facebook